becoming professor lai

fulfilling my childhood dreams

When I was five years old, I asked for an extra copy of a handwriting worksheet that Ms. D, my Kindergarten teacher, had given each of us. It was a simple worksheet filled with cursive letters in dotted lines for little hands to trace.

She asked me why I needed another one.

“I want to use it for my future students!” I told her, as if it were the most logical thought in the world.

In that moment—at the ripe age of five—I decided I wanted to be a teacher.

A childhood dream

I know my experience is somewhat unusual. As I grew up, I realized that most people’s childhood ambitions remained just that—a thing of childhood. And that most people don’t figure out what they want to do with their lives until much later. But for some reason, despite all the other dreams that surfaced over the years—architect, pianist, civil engineer—I always came back to this one.

As one gets older, childhood dreams tend to fade into a distant memory, and things like money and public opinion begin to take center stage. That’s not to say I never questioned my desire to become a teacher—I certainly had my share of existential crises in my 20s. Yet, despite being temporarily seduced by big tech salaries and the nobility of medicine, I always found my way back to that inner five-year-old, who envisioned herself in front of a classroom.

When passion meets opportunity

I was lucky enough to start teaching in my second year of college, when I became a TA for an introductory course in Cognitive Psychology. I’d taken the course as a freshman and was drawn to the professor’s infectious energy. Rice University had a much larger undergraduate than graduate population, so there was always demand for undergrad TAs. Prof. Z graciously welcomed me onto her teaching team, and I began holding office hours, grading assignments, and running exam review sessions. I discovered that I had a talent for breaking down complex ideas and the patience to explain concepts multiple times, in multiple ways. I got hooked on the dopamine rush of helping people learn, of watching the clouds of confusion part and clarity set in.

It was also in college that I discovered the joy of research. I did fine in my courses, but the repetitive structure of “learning for exams” felt uninspiring. It wasn’t until I joined my first research lab in the Department of Neuroscience at Baylor College of Medicine that I realized how science actually happens—not in memorizing facts, but in pursuing questions that don’t yet have answers. (I would later learn that good questions usually lead to even more questions.) I was incredibly fortunate to have an undergraduate PI1 who poured time and energy into mentoring me—guiding me through my first research projects, bringing me to conferences, and encouraging me through my crippling imposter syndrome. It was in those early college years, lying in my tiny dorm room bed late at night, that I began to imagine I could maybe—just maybe—become a professor one day.

In my senior year, I had the opportunity to design and teach my own course. I combined two of my passions—music and the brain—and created a course on the neuroscience of musical experience. For the first time, I had full control of a classroom: the syllabus, the content, the assignments, even the grades (I preferred a lack thereof)—and I loved it. Better yet, my students (who were my peers) loved it too.

So, I didn’t stop.

Facing doubt

During my PhD, I took every opportunity to engage in the classroom and grow as an educator. But as any professor will tell you, balancing research and teaching is no easy task. Many voices around me preached that teaching was a “waste of time” and “wouldn’t help me secure a faculty position.” They weren’t entirely wrong: teaching certainly took up a lot of my time—precious time that could’ve been spent publishing a few more papers.

I genuinely enjoyed research, but its rewards were sparse and unpredictable. Research studies took a long time to complete, and even once a project was “done” (like a work of art or a run-on sentence, they’re never really finished), it could take another 6 to 12+ months for a paper to get accepted in a journal. Though I managed to publish a decent amount during grad school, many of my projects reached dead ends and were eventually abandoned. To put it in nerd-speak, the input-to-output function was certainly not monotonic.

Teaching, on the other hand, offered a more structured rhythm. Each course had a clear beginning and end, and every finished lecture delivered a tangible sense of progress. I often found myself staying up on a Friday night to write a problem set I was genuinely excited about, spending hours giving thoughtful feedback on student research papers, or chatting with undergraduates who were brimming with curiosity.

To get a better sense of what faculty life was really like, I began having conversations with professors about how they balanced research and teaching. Many simply said, “I don’t.” Some admitted they had to sacrifice teaching quality for research productivity because “teaching doesn’t really matter for tenure.” Of course, there were brilliant researchers who were also gifted teachers—but they were few and far between.

I loved both teaching and research, but I also had to be realistic. Securing a traditional tenure-track job is difficult enough; even more so if you’re particular about where you want to live (which I was, given my two-body problem). I saw so many talented postdocs with stellar publication records struggle to land positions. And while many of my mentors assured me I could “make it” in academia, I started to wonder: Did I really want to “make it” in the traditional sense—grinding through the publish-or-perish pipeline—or did I want to pave my own path, one that played to my unique strengths and passions?

An open door

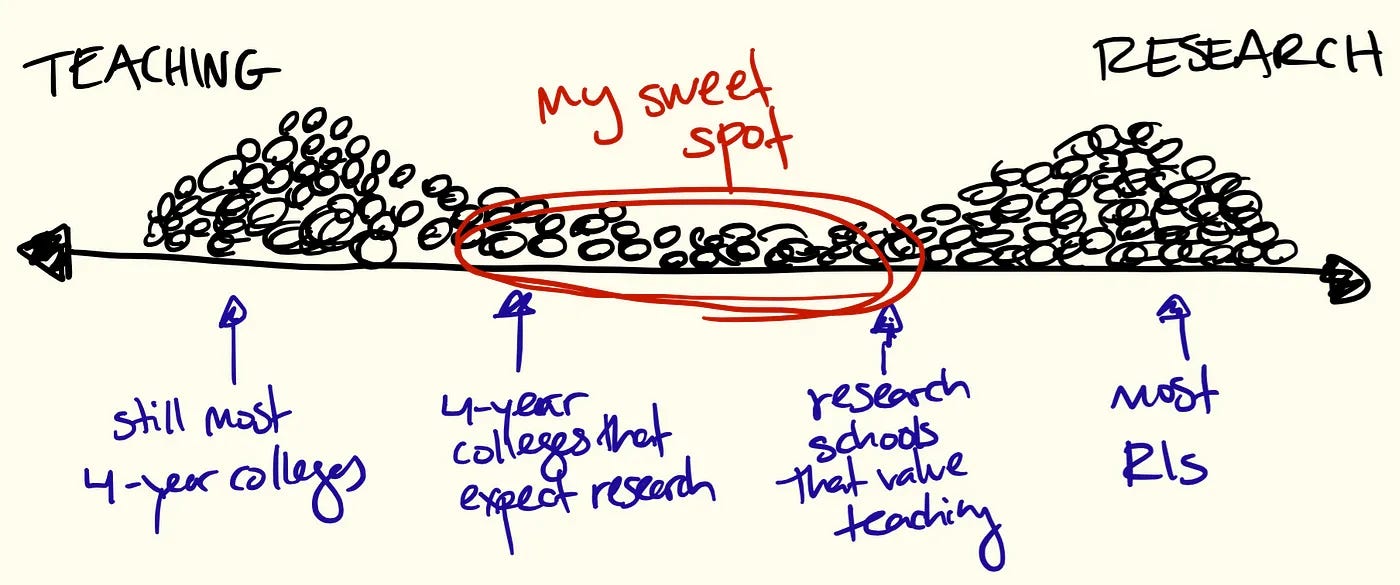

I began exploring career paths that would allow me to thrive as both a scientist and an educator—roles at institutions that truly valued and rewarded teaching, rather than treating it as a chore to be offloaded onto adjuncts. I knew that Primarily Undergraduate Institutions (PUIs), such as Liberal Arts Colleges (LACs) and Community Colleges (CCs), fit that description. But during my search process, I discovered a much broader spectrum of institutions and job descriptions that existed between the two extremes of research- and teaching-focused. There were four-year colleges that supported research activities, and research schools that highly valued teaching (my alma mater, Rice University, being one of them). I started feeling hopeful about career options I hadn’t previously heard of.

In the third year of my PhD, I connected with Ashley Juavinett and Shannon Ellis, two “teaching professors” at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). I hadn’t encountered a job title like that before, so I reached out to learn more. I was pleasantly surprised to discover that the University of California system had created a “tenure-track” teaching position2 that paralleled the traditional research-focused tenure track. The role emphasized excellence in teaching, course development, innovative curriculum design, and university service. But there was also support to run a small research program, and opportunities to mentor undergraduate and PhD students, sit on dissertation committees, and even write grants.

It sounded to me like a dream job.

But as with most things in life, timing is everything, and I knew these positions were few and far between. In my fifth year of my PhD, I signed up for a variety of academic job boards and kept an eye out for similar positions that aligned with my graduation timeline.

In November 2022, I came across a posting for an “Assistant Teaching Professor of Cognitive Science” position at UCSD. After a long conversation with my then-fiancé about how we would align our career trajectories, I decided to apply despite feeling wildly underqualified. After all, I hadn’t even finished my PhD yet! Hundreds of people apply for any given faculty position, and most applicants spend several years in postdoctoral training before going on the job market. I tried not to get my hopes up.

So it felt surreal when I received an invitation for a Zoom interview, and then for an on-campus visit with the department faculty. After 12 back-to-back interviews, a research talk, and a teaching demonstration, I found myself sipping a glass of wine over dinner, laughing and chatting with my potential future colleagues while watching a San Diego sunset through large, bow windows.

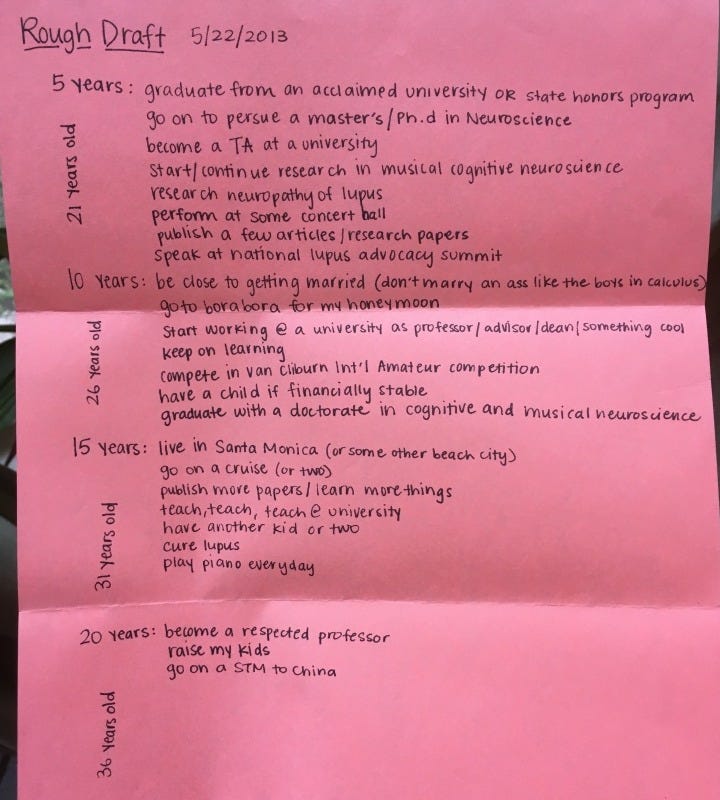

When I look back at the 20-year plan that I wrote at 16, I feel simultaneously embarrassed and proud. Embarrassed by my naïveté, yet proud that I stayed true to my teenage hopes and dreams. “Live in Santa Monica…(or some other beach city),” she declared.

A childhood dream

When I was five years old, I decided I wanted to be a teacher.

Dear five-year-old Lucy,

I want you to know that, after 23 years of school, you’re finally going to start your career as an Assistant Teaching Professor of Cognitive Science at the University of California, San Diego. You did it. 🥹

Yours truly,

Professor Lai

Acknowledgements

I get emotional just writing this—I know without a doubt that I wouldn’t be where I am today without the support of countless compassionate teachers who guided me throughout every stage of my life.

This section is for them.

To Ms. D, my kindergarten teacher, who encouraged the very first expressions of my dream. To my high school English teachers, who gifted me a love of writing. To my piano teachers, DD and DH, who blessed me with life lessons that can only be learned through music. You will forever hold a special place in my heart.

I am also deeply grateful to all my mentors from college and graduate school, who are incredible educators in their own right. To the scientists who raised me: David Dickman, who convinced me to attend Rice; Jeff Yau, my undergraduate PI, who nurtured my scientific potential; Sam Gershman, my PhD advisor, for supporting my teaching endeavors and cultivating my scientific independence; Venki Murthy, who invited me to co-design and teach a new course at Harvard; and Tari Tan, who gave me countless opportunities to grow as an educator. I truly stand on the shoulders of giants.

To the professors that opened my eyes to a teaching-focused academic career: Stephen Chen at Wellesley College, who offered his insight into teaching at liberal arts colleges, as well as valuable advice on life, career, and faith. Ashley Juavinett and Shannon Ellis, my soon-to-be colleagues, who first opened my eyes to this career path and shared a wealth of wisdom along the way. You inspire me to keep growing as an educator.

And finally, to my students: you shaped me into the teacher I am today. From my peers at Rice who trusted me as an undergrad TA, to the students at Harvard who allowed me to experiment with new teaching styles and methods. I promise to carry that same energy, curiosity, and enthusiasm to the classroom at UCSD.

There are many, many more people I could thank, but I would run out of metaphorical ink before I could name them all.

Thank you all, from the bottom of my heart. I can only hope to pay forward even a fraction of the time, care, and energy you’ve poured into me.

Principal Investigator, or the head of a research lab. PIs are usually professors that direct research agendas and oversee everything from grant funding to data analysis to publications.

Officially, these positions are called “Lecturer with Potential Security of Employment.”

Congratulations Lucy! Only a few have the determination and courage to pursue their lifelong dreams. Once again, I am happy that I got the chance to get to know you, even if it was for a very short time. I wish you all the best in this new stage of your life, I know you’ll crush it.

Looking forward to another boba date!

Congrats Professor Lai ☺️